Contributor: Bradford Boehme, Local Historian and Pioneer Descendant

“They stand tall and picturesque; the houses of Medina County are silent monuments to the pioneers who settled here in the mid-19th century. More than any recently made memorial to their brave actions, the strong homes that the colonists built with their own hands will keep their spirit in the minds of people forever. I have always been intrigued by the local architecture and the people responsible, namely, my ancestors.”

I wrote these words in 1998 when I was in college and performed my first in-depth research into the architecture of Medina County for a paper in a class called Modes of Inquiry at the University of Texas at San Antonio. I chose to inquire about the homestead of my ancestors, great-great-great-grandparents Jacob and Marthe Haby, and the Haby Settlement. Each question answered in my research led to a dozen unanswered questions, which subsequently revealed much information about the families, their growth and the construction they left behind as a part of their legacy in Texas.

The first homes built by the pioneers were crude huts. I have come to describe some of their early huts as jacals. Jacals were simple huts with vertically stacked wooden pickets that were chinked with mud and straw. Often the roof was made of thatched bear or carrizo cane or prairie grasses. Door and window openings were simple and few with no glass and often a cattlehide served as the door. The floor was bare-stamped earth and furnishings were rudimentary. There is no example of this early construction remaining in Medina County today. However, a few photographs remain.

The pioneers in Medina County came from a variety of cultures with differing degrees of wealth and that is reflected in their homes. The need for housing quickly on the frontier forced every pioneer to expedite the construction of a simple dwelling. The jacal or a tent was often their first home and some families remained in their primitive homes for longer than others.

Depiction of an original jacal home

The existing photographs and paintings of jacals come to us from various sources. The Schott and Rothe jacals still in existence in the early 1900s were photographed at that time, but they were no longer in use as homes. The Schott jacal became a small feed or tack room in their pens and the Rothe jacal became a corn crib for the Boehme farm.

In Medina County, very often any structure that required time or money to build was used and reused as often as possible. In San Antonio, jacals continued to serve as housing at the turn of the century.

In very short order, the pioneer families in Medina County turned to small homes of log or limestone, or a combination of both materials, as a primary residence. The UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures features an exhibit showcasing a “casa fuerte” or a small fort-like building with stone walls, a strong door and a few small gun-slit-style windows. Some of these small stone buildings were constructed at the same time as the jacals and early log homes.

Geography and access to building materials, or even the lack of materials, contributed to the style of home that was built. If a family’s farm was in or near the Hill Country or along the bluffs along the rivers and creeks, an abundance of both white and yellow limestone could be gathered. Only farms along the main rivers and creeks allowed the opportunity to harvest cypress trees for logs or to process them further into beams and boards. Mesquite trees large enough to process into usable lumber and pickets were to be found in many places.

Homes constructed in the late 1840s to the mid-1850s were small and often built by the hands of the family who would live there. While many colonists were destined to work as farmers and ranchers, some pioneers were skilled stone masons, carpenters and woodsmen. A sturdy and comfortable house without much luxury or refinement was the desired result.

The home built by an experienced mason would have straight walls — not wavy and unsquared as could be found in a home built by a farmer with fewer masonry skills. You can find these examples in many of the early homes in Medina County and can make assumptions about which level of home-building experience was present for its construction.

Regardless of whether the home was built of stone or log, the dwelling was a single-room structure, with perhaps a loft, and included a fireplace or small wood-burning stove. Simple plank doors and sometimes windows of glass imported from San Antonio were used in the openings of the house.

The elegant rural architectural lines of the “saltbox,” or as we say in Medina County, “Alsatian” style, was first attributed to the home that the Revs. Claude Dubuis and Matthew Chazell built with their own hands in the summer of 1847. The home still stands on Angelo Street across from the first St. Louis Catholic Church in Castroville.

Many stories have been written about the pair of priests going out to collect stone with a cart and being able to load the cart by removing the wheels and lowering the deck to the ground. They would then push and lever stone into the cart, and by using jacks and cribbing, could raise the cart enough to reattach the wheels and transport their building materials back to the site.

The men’s energy and creativity in successfully building themselves a comfortable and elegant home inspired other people to do the same and created a sense of permanence in Castroville. In mid-1844, workers completed what became the Burger house on Florence Street and stayed in the home while they were completing other houses, including the stone house that Henri Castro commissioned in 1845. Louis Huth built at least a portion of the home in 1846.

The latter-1840s witnessed a flurry of building in Castroville, Quihi, Vandenburg and D’Hanis. The construction pattern was much the same in all the villages of the Castro Colonies. The tents and jacal huts gave way quickly to sturdy stone structures. By the mid-1850s, larger homes and businesses began to be built.

George L. Haass built his store in 1849, and the same year, Cesar Monod built a single-story store building across from Haass. In 1852, the Tarde Hotel was built in 1852, and two years later, Haass and Quintle built their stone dam and gristmill on the Medina River. Gerhard Ihnken hired Merian and Chassard to build his two-story stone store downstairs and home upstairs with a large warehouse basement.

In the countryside and within the villages, the pioneers mostly built in progression as the means or need came along. Often, a single-room home or something as small as a casa fuerte, was given an addition to create a larger home or store complex.

Stone mason Jacob Bippert completed his one-room house in 1847. He received an additional lot as payment for his work on the first St. Louis Church. In 1872, the property was sold to Henry Kueck who added two rooms with fireplaces and replaced the dirt floors with stone and cypress lumber. By the mid-1850s and through the 1860s, the colonists were firmly established.

As they organized and various families discovered or purposefully purchased properties with marketable natural resources, the process of obtaining building materials was streamlined and marketed.

Joseph Meyer built a stone home on his 40-acre homestead on Lower LaCoste Road in 1855. The Meyers also built a kiln for baking limestone on the bank of the Medina River on their homestead. Other kilns are known to exist in the area, including one on the Bourquin farm north of Rio Medina and another one on the Wurzbach/Crow property south of Rio Medina.

The kilns were constructed and used in the same manner. Made of stone and lined with mortar, the kiln was a simple cylinder of stone built into the bank so that the top and bottom of the cylinder could be rolled to with a wagon. The bottom of the oven had an opening that would be closed with stone when firing the limestone. The top was where you could load the kiln with raw stone and cordwood.

After the limestone was baked sufficiently, the bottom of the oven would be open, and the finished product of lime would be crushed and raked out into a wagon to haul to the work site where a slacking pit was built. This consisted of a long and narrow trench being dug into the earth and its sides lined with lime plaster so that the trench could hold water. The trough or pit was filled with the lime from the kiln and allowed to slack with the addition of water. Sand from the river bottom was added to the pit to create the mortar that was used in the stone masonry for the walls of a home.

Archeologists under Dr. Ruth Van Dyke performed various archaeological digs on the Jacob Biry homesite on Paris Street in Castroville. In the backyard of the 1850s-era stone home, a slacking pit was discovered very near to the house. The mortar-lined slacking pit had been built and used during construction and remained open until the 1930s when it was used as a trash pit by the homeowners and subsequently covered with earth once full of trash.

One story tells of a priest interrupting class dressed in his long flannel shirt bespattered with mortar to recruit some strong young men from the Catholic school to help him carry more buckets of sand from the Medina River bottom to his slacking pit.

A specific limestone quarry — in other words, a large hole in the side of a limestone hillside from years and years of quarrying activity and building in Medina County — does not exist. Tons of limestone and fieldstone were gathered throughout the last half of the 19th century but central commercialized stone operation was not practical due entirely to transportation. The closer to the building site that the material could be obtained, the easier it would be to haul the material by ox or mule-drawn wagon or cart. Often it is said that a pioneer farmer would end his day by dragging home a sled loaded with stone that was removed from the field. That made farming easier and made use of the stone that was in his way in the field.

Two particular stone harvesting sites are located on what was known as the Tondre farm and the Burrell Pasture just northwest of Castroville. These “quarry sites” were used to obtain and shape limestones used in the construction of the third St. Louis Church in 1868. Presumably, other homes and businesses were built of the stone from these sources and it can be seen that this area is the closest of the limestone Hill Country to the site of Castroville which facilitated hauling from within close proximity.

In these locations, there are natural shelves of limestone one to two feet thick with a flat top and bottom jutting out of the hillsides. A two-person work crew would wield a sledgehammer and a star-bit stone chisel to bore holes into the shelves of stone. A little black powder in the borehole and the subsequent explosion could yield relatively square chunks of hard limestone block which could then be further dressed or cleaned up with hammer and chisel.

Some homes and even some portions of homes were built with softer caliche stones. There is a layer of caliche about three feet below the surface in many areas to the west of Castroville. Some layers of caliche are exposed and access to the soft stone is made easier without the need for excavating. This type of caliche stone can be shaped with a simple wood cutting saw but its use in constructing walls requires a good layer of mortar on the exterior to protect the soft stone from deteriorating. There are areas, specifically around Quihi and Vandenburg, where the source of stone building material was yellow limestone. Rubblestone was often collected from the surface anywhere available. A technique of using a few nice and square stones in the corners of the walls, around fireplace chimney flues, door and window openings, with rubble stone used in the straight runs of the walls and generously plastered over with mortar, created fully functional stone homes.

There are many features of the homes in the area hat are consistent throughout Medina County. Locally obtained building materials are the most commonly observed feature of local architecture for obvious reasons. Some of the homes went without porches just as their homes in Germany and France may have been, while in Texas, some families realized the need for shade from the hot summer sun and added porches to their homes.

Some homes have root or wine cellars and some do not. Many of the early homes were roofed with cedar or cypress shingles. Some very early ones began with thatched rooves. Most of the homes included cheesecloth ceilings which were used to catch the mice, spiders and scorpions that might fall from the roof onto unsuspecting victims below.

Almost every roof in Medina County was decked with rough-sawn cypress which retained its original “live edge” dimension from its log form. It made sense to the sawyer to make use of the entire width of the log he was sawing for roof decking and it was unnecessary to square all four sides of the log. The shingle manufacturing industry was a fairly large business in the Hill Country and along the rivers. There was a small camp of cypress shingle makers on the Medina River just before Castroville’s founding. A flood had washed away the camp and a few of the early homes were roofed with shingles salvaged from drifts in the river where the shingles had ended up after the flood. As the shingle roofs began to fail, new shingle roofs were installed.

Beginning in the 1870s, August Knoblock and later, people living in the Some homes reached the upstairs portions by interior staircases. Some were located on an exterior wall while others simply used a ladder that could be pulled up after the homeowner settled into the loft for the night — a simple defensive measure.

Shutters were a common feature of many of the pioneer homes. The shutters were fully functional and used in both defense and temperature adjustment to the climate of the home.

A unique feature created by some builders, or perhaps just one stone mason who has never been identified specifically, was created by running a chimney flume of the fireplace or wood stove through hollow flues formed in the thick stone walls of the home. There are examples of fireplaces in corners of rooms with the chimney running through the wall at an angle to the central eve of the roof. There is an example or two where a clever mason had a fireplace with a window right above it and just passed the flue through the wall around the window and up to the center of the eve.

Some builders included iron rods through the house along the joists of the second floor and anchored them into the stone walls with “S” shaped wall ties. The “S” shaped anchor can be seen on the exterior walls and a turnbuckle is often located in the iron rod within the building. These wall ties could be tightened on occasion to prevent the stone walls from bowing out.

At least two rose windows of stained glass can be found in Castroville, one in the home of Fr. Claude Dubuis and the other in the 1873 convent of the Congregation of Divine Providence.

In most cases, the fireplaces in the front rooms of the home had a ground-level hearth and were used to warm the home on cold winter days. The long and narrow “lean-to” portion of the home often served as the kitchen and in many homes, the fireplace in the kitchen had a raised hearth to make it easier to cook without having to bend over to the floor level.

Just like each family in Castroville has unique tendencies and traditions, each family and home builder included nuances of their own to make their home unique.

In 1868, Rev. Peter Richard decided that the second St. Louis Church needed replacement. Richard had engineered the St. Louis Church and designed it to accommodate his parish for both his present and the future.

In 1870, both the church and Sr. Andrew Feltin, CDP, completed their original Motherhouse, and in 1873, a much larger convent replaced the original which then became the first St. Louis Catholic School.

The three large construction projects required and attracted many professional stone masons and carpenters. Joseph Schorp is credited with the position of head carpenter and supervisor while Jean Merian is listed as one of the professional stone masons charged with the intricate stonework on the walls and steeple for the St. Louis Church.

Parishioners were called upon to give money while others donated stone, sand, lime, lumber and other materials. Many gave their time as laborers. The 1870 census of Castroville lists eight masons, seven carpenters and one tinsmith and represents a very large percentage of the population in town making a living professionally as builders and not farmers.

In the late 1860s through the 1870s, the model or style of the home remained the same with the “Alsatian” style the predominant architecture represented. However, the size of the homes increased significantly and many of the smaller homes received additions.

The Louis Haller house on Fiorella Street in Castroville was completed in 1875 and a distinct change in the stonework on the sides of the home can be seen where the house was increased in size and height.

The convent and church projects spurred the construction industry in Medina County. The increase in professional craftsmen in the area was sustained during their construction. Following completion, these professionals were kept busy in the area building substantial homes for the pioneers who were growing wealthier and more prosperous following the last of what was a poorer economy during and immediately after the Civil War.

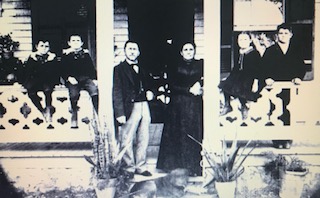

In the Haby Settlement, the Jacob and Caroline Haby family had a very large stone home built in the “Alsatian” style in the 1870s by the professionals in the area. Their new home replaced an original log cabin and accommodated their family which eventually grew to include 17 children. To this day, the square and true stone walls and fine woodworking are intact with every window and door still functioning.

The coming of the Gulf, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railroad in the late 1870s was a hot topic in Castroville. Many of the residents of Castroville were against the railroad for various reasons but the largest contingent was anti-railroad because they worked as wagon freighters. Some of the more progressive residents, including the merchants, hotel keepers, masons and carpenters, were excited about the obvious advantage of having the railroad pass through Castroville.

Gerhard Ihnken had been a very active entrepreneur and civic leader since his arrival in Castroville in 1846. Ihnken was a man of means upon his arrival and had excelled in the cattle business, cotton farming, custom grain harvesting, cotton ginning, sawing and planning millwork, mercantile businesses, mule raising and training, cattle butchering and land speculation. By the time the railroad approached, Ihnken owned roughly 50 lots in the town of Castroville. He distributed his ranching empire equally among his children and began an endeavor with an original name, “The Castroville Construction Company.” He intended to develop his lots in town for the people who most definitely would be coming with the railroad.

Unfortunately, the railroad required a $100,000 bond to be put up by the citizens of Castroville. This cost, along with the majority of the populace in opposition to the idea, led the railway to bypass Castroville. And to add insult to injury, the railmen routed the track a full five-mile radius around and away from the town to cut off all economic benefit to Castroville. Ihnken returned to his mercantile and stock-raising businesses, and the trunk of tools for his Castroville Construction Co went to the barn. The trunk and tools are stored in my barn, a reminder of what could have been.

Castroville’s decision to deny the railmen resulted in the Carle brothers moving away with their respective stores. The Congregation of Divine Providence relocated their Motherhouse to San Antonio. With the growth of the towns along the rail line, including Hondo, which was centrally located in Medina County, the decision was made in 1892 to remove the county seat of government from Castroville and install it in Hondo. Even the wagon freighters lost their industry to the railroad but that was going to happen regardless of whether it passed through Castroville or not.

While Castroville lost economically, the city gained in charm. It’s not known how badly the railroad would have damaged the original architecture of Castroville and perhaps the new construction would have fit right in with the tradition that had existed in Castroville since its inception. In any case, Castroville disincorporated its city government and slipped into a sleepy existence as the little Alsatian village of Texas, a time capsule of a town!

Shutters were a common feature of many of the pioneer homes. The shutters were fully functional and used in both defense and temperature adjustment to the climate of the home.

A unique feature created by some builders, or perhaps just one stone mason who has never been identified specifically, was created by running a chimney flume of the fireplace or wood stove through hollow flues formed in the thick stone walls of the home. There are examples of fireplaces in corners of rooms with the chimney running through the wall at an angle to the central eve of the roof. There is an example or two where a clever mason had a fireplace with a window right above it and just passed the flue through the wall around the window and up to the center of the eve.

Some builders included iron rods through the house along the joists of the second floor and anchored them into the stone walls with “S” shaped wall ties. The “S” shaped anchor can be seen on the exterior walls and a turnbuckle is often located in the iron rod within the building. These wall ties could be tightened on occasion to prevent the stone walls from bowing out.

At least two rose windows of stained glass can be found in Castroville, one in the home of Fr. Claude Dubuis and the other in the 1873 convent of the Congregation of Divine Providence.